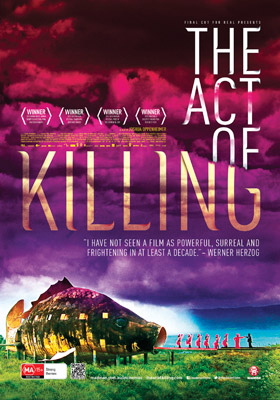

Haji Anif, Syamsul Arifin and Sakhyan Asmara The Act Of Killing

Haji Anif, Syamsul Arifin and Sakhyan Asmara The Act Of Killing

Cast: Haji Anif, Syamsul Arifin, Sakhyan Asmara

Director: Joshua Oppenheimer

Rated: MA

Running Time: 159 minutes

Synopsis: In this chilling and inventive documentary, executive produced by Werner Herzog (Grizzly Man) and Errol Morris (The Fog of War), the unrepentant former members of Indonesian death squads are challenged to re-enact some of their many murders in the style of the American movies they love.

In the 1960s Anwar Congo was a leader in Indonesia's pro-regime paramilitary group, Pancasila Youth who, along with his band of dedicated followers, was amongst those who participated in the murder and torture more than a million alleged Communists, ethnic Chinese and intellectuals. Proud of their deeds, which have still gone unpunished, Anwar and his pals are lauded as national heroes, and are delighted when the filmmakers ask them to re-enact these murders for their documentary – in any genre they desire. Initially Anwar and his friends enthusiastically take up the challenge using hired actors, making elaborate sets and costumes, but eventually as the movie violence is played out and reconstructed, Anwar's conscience begins to stir and feelings of remorse surface.

The Act Of Killing

Release Date: October 3rd, 2013

About The Film

In a country where killers are celebrated as heroes, the filmmakers challenge unrepentant death squad leaders to dramatise their role in genocide. The hallucinatory result is a cinematic fever dream, an unsettling journey deep into the imaginations of mass-murderers and the shockingly banal regime of corruption and impunity they inhabit.

Anwar Congo and his friends have been dancing their way through musical numbers, twisting arms in film noir gangster scenes, and galloping across prairies as yodeling cowboys. Their foray into filmmaking is being celebrated in the media and debated on television, even though Anwar Congo and his friends are mass murderers.

Medan, Indonesia. When the government of Indonesia was overthrown by the military in 1965, Anwar and his friends were promoted from small-time gangsters who sold movie theatre tickets on the black market to death squad leaders. They helped the army kill more than one million alleged communists, ethnic Chinese, and intellectuals in less than a year. As the executioner for the most notorious death squad in his city, Anwar himself killed hundreds of people with his own hands.

Today, Anwar is revered as a founding father of a right-wing paramilitary organisation that grew out of the death squads. The organisation is so powerful that its leaders include government ministers, and they are happy to boast about everything from corruption and election rigging to acts of genocide.

The Act Of Killing is about killers who have won, and the sort of society they have built. Unlike ageing Nazis or Rwandan génocidaires, Anwar and his friends have not been forced by history to admit they participated in crimes against humanity. Instead, they have written their own triumphant history, becoming role models for millions of young paramilitaries. The Act Of Killing is a journey into the memories and imaginations of the perpetrators, offering insight into the minds of mass killers. And The Act Of Killing is a nightmarish vision of a frighteningly banal culture of impunity in which killers can joke about crimes against humanity on television chat shows, and celebrate moral disaster with the ease and grace of a soft shoe dance number.

A Love of Cinema. In their youth, Anwar and his friends spent their lives at the movies, for they were 'movie theatre gangsters": they controlled a black market in tickets, while using the cinema as a base of operations for more serious crimes. In 1965, the army recruited them to form death squads because they had a proven capacity for violence, and they hated the communists for boycotting American films – the most popular (and profitable) in the cinemas.

Anwar and his friends were devoted fans of James Dean, John Wayne, and Victor Mature. They explicitly fashioned themselves and their methods of murder after their Hollywood idols. And coming out of the midnight show, they felt 'just like gangsters who stepped off the screen". In this heady mood, they strolled across the boulevard to their office and killed their nightly quota of prisoners. Borrowing his technique from a mafia movie, Anwar preferred to strangle his victims with wire.

In The Act Of Killing, Anwar and his friends agree to tell us the story of the killings. But their idea of being in a movie is not to provide testimony for a documentary: they want to star in the kind of films they most love from their days scalping tickets at the cinemas. We seize this opportunity to expose how a regime that was founded on crimes against humanity, yet has never been held accountable, would project itself into history.

And so we challenge Anwar and his friends to develop fiction scenes about their experience of the killings, adapted to their favourite film genres – gangster, western, musical. They write the scripts. They play themselves. And they play their victims.

Their fiction filmmaking process provides the film's dramatic arc, and their film sets become safe spaces to challenge them about what they did. Some of Anwar's friends realize that the killings were wrong. Others worry about the consequence of the story on their public image. Younger members of the paramilitary movement argue that they should boast about the horror of the massacres, because their terrifying and threatening force is the basis of their power today. As opinions diverge, the atmosphere on set grows tense. The edifice of genocide as a 'patriotic struggle", with Anwar and his friends as its heroes, begins to sway and crack.

Most dramatically, the filmmaking process catalyses an unexpected emotional journey for Anwar, from arrogance to regret as he confronts, for the first time in his life, the full implications of what he's done. As Anwar's fragile conscience is threatened by the pressure to remain a hero, The Act Of Killing presents a gripping conflict between moral imagination and moral catastrophe.

Production Notes

First Encounter with the 1965-66 Massacres – The Globalisation Tapes

In 2001-2002, Christine Cynn and I went to Indonesia for the first time to produce The Globalisation Tapes (2003), a participatory documentary project made in collaboration with the Independent Plantation Workers Union of Sumatra. Using their own forbidden history as a case study, these Indonesian filmmakers worked with us to trace the development of contemporary globalisation from its roots in colonialism to the present.

The Globalisation Tapes exposes the devastating role of militarism and repression in building the global economy, and explores the relationships between trade, third-world debt, and international institutions like the IMF and the World Trade Organisation. Made by some of the poorest workers in the world, the film is a lyrical and incisive account of how our global financial institutions shape and enforce the corporate world order.

Several scenes in The Globalisation Tapes reveal the earliest traces of the methods we refined in the shooting of The Act Of Killing: plantation workers stage a satirical commercial for the pesticide that poisons them; worker-filmmakers pose as World Bank agents who offer microfinance to -develop' local businesses – offers that are both brutal and absurd, yet tempting nonetheless.

While shooting and editing The Globalisation Tapes, we discovered that the 1965-66 Indonesian massacres were the dark secret haunting Indonesia's much-celebrated entrance into the global economy. One of the military's main objectives in the killings was to destroy the anti-colonial labour movement that had existed until 1965, and to lure foreign investors with the promise of cheap, docile workers and abundant natural resources. The military succeeded (The Globalisation Tapes is a testament to the extraordinary courage of the plantation worker-filmmakers as they challenge this decades-long legacy of terror and try to build a new union).

The killings would come up in discussions, planning sessions, and film shoots nearly every day, but always in whispers. Indeed, many of the plantation workers were themselves survivors of the killings. They would discretely point out the houses of neighbours who had killed their parents, grandparents, aunts, or uncles. The perpetrators were still living in the same village and made up, along with their children and protégés, the local power structure. As outsiders, we could interview these perpetrators – something the plantation workers could not do without fear of violence. In conducting these first interviews, we encountered the pride with which perpetrators would boast about the most grisly details of the killings. The Act Of Killing was born out of our curiosity about the nature of this pride – its clichéd grammar, its threatening performatives, its frightening banality.

The Globalisation Tapes was a film made collectively by the plantation workers themselves, with us as facilitators and collaborating directors. The Act Of Killing was also made by working very closely with its subjects, while in solidarity and collaboration with the survivors' families. However, unlike The Globalisation Tapes, The Act Of Killing is an authored work, an expression of my own vision and concerns regarding these issues.

The Beginnings of The Act Of Killing

The Beginnings of The Act Of Killing

By the time I first met the characters in The Act Of Killing (in 2005), I had been making films in Indonesia for three years, and I spoke Indonesian with some degree of fluency. Since making The Globalisation Tapes, Christine Cynn, fellow filmmaker and long-time collaborator Andrea Zimmerman and I had continued filming with perpetrators and survivors of the massacres in the plantation areas around the city of Medan. In 2003 and 2004, we filmed more interviews and simple re-enactments with Sharman Sinaga, the death squad leader who had appeared in The Globalisation Tapes. We also filmed as he introduced us to other killers in the area. And we secretly interviewed survivors of the massacres they committed.

Moving from perpetrator to perpetrator, and, unbeknownst to them, from one community of survivors to another, we began to map the relationships between different death squads throughout the region, and began to understand the process by which the massacres were perpetrated. In 2004, we began filming Amir Hasan, the death squad leader who had commanded the massacres at the plantation where we made The Globalisation Tapes.

In late 2004, Amir Hasan began to introduce me to killers up the chain of command in Medan. Independently in 2004, we began contacting -veterans' organisations of death squad members and anti-leftist activists in Medan. These two approaches allowed us to piece together a chain of command, and to locate the surviving commanders of the North Sumatran death squads. In early interviews with the veterans of the killings (2004), I learned that the most notorious death squad in North Sumatra was Anwar Congo and Adi Zulkadry's Frog Squad (Pasukan Kodok).

During these first meetings with Medan perpetrators (2004 and 2005), I encountered the same disturbing boastfulness about the killings that we had been documenting on the plantations. The difference was that these men were the celebrated and powerful leaders not of a small rural village, but of the third largest city in Indonesia (Greater Medan has a population of over four million people).

Our starting point for The Act Of Killing was thus the question: how had this society developed to the point that its leaders brag about their own crimes against humanity, recounting atrocities with a cheer that is both celebratory and also intended as a threat?

Overview and Chronology of the Methods used in The Act Of Killing

Building on The Globalisation Tapes and our film work outside Indonesia, we had developed a method in which we open a space for people to play with their image of themselves, re- creating and re-imagining it on camera, while we document this transformation as it unfolds. In particular, we had refined this method to explore the intersection between imagination and extreme violence. In the early days of research (2005), I discovered that the army recruited its killers in Medan from the ranks of movie theatre gangsters (or preman bioskop) who already hated the leftists for their boycott of American movies – the most profitable in the cinema. I was intrigued by this relationship between cinema and killings, although I had no idea it would be so deep. Not only did Anwar and his friends know and love the cinema, but they dreamed of being on the screen themselves, and styled themselves after their favourite characters. They even borrowed their methods of murder from the screen.

Of course, I began by trying to understand in as much detail as possible Anwar and his friends' roles in the killings and, afterwards, in the regime they helped to build. Among the first things I did was to bring them to the former newspaper office directly across the road from Anwar's old cinema, the place where Anwar and his friends killed most of their victims. There, they demonstrated in detail what they had done. Although they were filming documentary re-enactment and interviews, during breaks I noticed that they would muse about how they looked like various movie stars – for instance, Anwar compared his protégé and sidekick, Herman, to Fernando Sancho.

To understand how they felt about the killings, and their unrepentant way of representing them on film, I screened back the unedited footage of these early re-enactments, and filmed their responses. At first, I thought that they would feel the re-enactments made them look bad, and that they might quit the film, or else come to a more complex place morally and emotionally. I was startled by what actually happened. As we see in the film, Anwar was mostly anxious that he should look young and fashionable. Instead of any explicit moral reflection, the screening led him and Herman spontaneously to suggest a better, and more elaborate, dramatisation.

To explore their love of movies, I screened for them scenes from their favourite films at the time of the killings – Cecil B. DeMille's Samson and Delilah and, ironically, The Ten Commandments topped the list – recording their commentary and the memories these films elicited. Through this process, I came to realise why Anwar was continually bringing up these old Hollywood films whenever I filmed re-enactments with them: he and his fellow movie theatre thugs were inspired by them at the time of the killings, and had even borrowed their methods of murder from the movies. This was such an outlandish and disturbing idea that I in fact had to hear it several times before I realised quite what Anwar and his friends were saying.

He described how he got the idea of strangling people with wire from watching gangster movies. In a late-night interview in front of his former cinema, Anwar explained how different film genres would lead him to approach killing in different ways. The most disturbing example was how, after watching a 'happy film like an Elvis Presley musical," Anwar would 'kill in a happy way."

In 2005, I also discovered that the other paramilitary leaders (not just the former movie theatre gangsters) had other personal and deep-seated relationship to movies. Ibrahim Sinik, the newspaper boss who was secretary general of all the anti-communist organisations that participated in the killings, and who directly gave the orders to Anwar's death squad, turned out to be a feature film producer, screenwriter, and former head of the Indonesian Film Festival.

In addition to all this, Anwar and his friends' idea of being in a film about the killings was essentially to act in dramatisations of their pasts – both as they remember them, and as they would like to be remembered (the most powerful insights in The Act Of Killing probably come in those places where these two agendas radically diverge). As described, the idea of dramatisations came up quite spontaneously, in response to viewing the rushes from Anwar's first re-enactments of the killings. But it would be disingenuous to claim that we facilitated the dramatisations only because that's what Anwar and his friends wanted to do. Ever since we produced THE GLOBALIZATION TAPES, the thing that most disturbed us was the way the killers we filmed recounted their stories. One had the feeling that we weren't hearing memories, receiving performances. We understood that the purpose of these performances was to assert impunity, to create a threatening image, to perpetuate the autocratic regime that had begun with the massacres themselves. Boasting is a means by which regimes of terror sustain themselves.

We sensed that the methods we had developed for incorporating performance into documentary might, in this context, yield powerful insights into the mystery of the killers' boastfulness, the nature of the regime of which they are a part, and, most importantly, the nature of human -evil' itself.

We sensed that the methods we had developed for incorporating performance into documentary might, in this context, yield powerful insights into the mystery of the killers' boastfulness, the nature of the regime of which they are a part, and, most importantly, the nature of human -evil' itself. So, having learned that even their methods of murder were directly influenced by cinema, we challenged Anwar and his friends to make the sort of scenes they had in mind. We created a space in which they could devise and star in dramatisations based on the killings, using their favourite genres from the medium. Fiction would be the canvas on which they could paint their own portrait and stand back and look at it.

We started to suspect that performance played a similar role during the killings themselves, making it possible for Anwar and his friends to absent themselves from the scene of their crimes, while they were committing them. Thus, performing dramatisations of the killings for our cameras became a re-living of a mode of performance they had experienced in 1965, when they were killing. This obviously gave the experience of performing for our cameras a deeper resonance for Anwar and his friends than we had anticipated.

And so, in The Act Of Killing, we worked with Anwar and his friends to create such scenes for the insights they would offer, but also for the tensions and debates that arose during the process – including Anwar's own devastating emotional unravelling. This created a safe space, in which all sorts of things could happen that would probably elude a more conventional documentary method. The protagonists could safely explore their deepest memories and feelings (as well as their blackest humour). I could safely challenge them about what they did, without fear of being arrested or beaten up. And they could challenge each other in ways that were otherwise unthinkable, given Sumatra's political landscape.

Anwar and his friends could direct their fellow gangsters to play victims, and even play the victims themselves, because the wounds are only make-up, the blood only red paint, applied only for a movie. Feelings far deeper than those that would come up in an interview would surface unexpectedly. One reason the emotional impact was so profound came from the fact that this production method required a lot of time – the filmmaking process came to define a significant period in the participants' lives. This meant that they went on a deeper journey into their memories and feelings than they would in a film consisting largely of testimony and simple demonstration. Different scenes used different methods, but in all of them it was crucial that Anwar and his friends felt a sense of fundamental ownership over the fiction material. The crux of the method is to give performers the maximum amount of freedom to determine as many variables as possible in the production (storyline, casting, costumes, mise-en-scene, improvisation on set).

Whenever possible, I let them direct each other, and used my cameras to document their process of creation. My role was primarily that of provocateur, challenging them to remember the events they were performing more deeply, encouraging them to intervene and direct each other when they felt a performance was superficial, and asking questions between takes – both about what actually happened, but also about how they felt at the time, and how they felt as they re-enacted it.

We shot in long takes, so that situations could evolve organically, and with minimal intervention from ourselves. I felt the most significant event unfolding in front of the cameras was the act of transformation itself, particularly because this transformation was usually plagued by conflict, misgivings, and other imperfections that seemed to reveal more about the nature of power, violence, and fantasy than more conventional documentary or investigative methods. For this same reason, we also filmed the pre-production of fiction scenes, including castings, script meetings, and costume fittings. Make-up sessions too were important spaces of reflection and transformation, moments where the characters slip down the rabbit hole of self-invention.

In addition, because we never knew when the characters would refuse to take the process further, or when we might get in trouble with the military, we filmed each scene as though it might be the last, and also everything leading up to them (not only for the reasons above), because often we didn't know if the dramatisation itself would actually happen. We also felt that the stories we were hearing – stories of crimes against humanity never before recorded – were of world historical importance.

After almost every dramatisation, we would screen the rushes back to them, and record their responses. We wanted to make sure they knew how they appeared on film, and to use the screening to trigger further reflection. Sometimes, screenings provoked feelings of remorse (as when Anwar watches himself play the victim during a film noir scene) but, at other times, as when we screened the re-enactment of the Kampung Kolam massacre to the entire cast, the images were met with terrifying peals of laughter.

Most interestingly, Anwar and his friends discussed, often insightfully, how other people will view the film, both in Indonesia and internationally. For example, Anwar sometimes commented on how survivors might curse him, but that 'luckily" the victims haven't the power to do anything in today's Indonesia.

The gangster scenes were wholly improvised. The scenarios came from the stories Anwar and his friends had told each other during earlier interviews, and during visits to the office where they killed people. The set was modelled on this interior. For maximum flexibility, our cinematographer lit the space so that Anwar and his friends could move about freely, and we filmed them with two cameras so that they could fluidly move from directing each other to improvised re-enactments to quiet, often riveting reflection after the improvisation was finished.

The large-scale re-enactment of the Kampung Kolam massacre was made using a similar improvisational process, with Anwar and his friends directing the extras. What we didn't expect was a scene of such violence and realism; so much so that it proved genuinely frightening to the participants, all of whom were Anwar's friends from Pancasila Youth, or their wives and children. After the scene, we filmed participants talking amongst themselves about how the location of our re-enactment was just a few hundred meters from one of North Sumatra's countless mass graves. The woman we see fainting after the scene felt she had been possessed by a victim's ghost. The paramilitary members (including Anwar) thought so, too. The violence of the re-enactment conjured the spectres of a deeper violence, the terrifying history of which everybody in Indonesia is somehow aware, and upon which the perpetrators have built their rarefied bubble of air conditioned shopping malls, gated communities, and 'very, very limited" crystal figurines.

The process by which we made the musical scenes (the waterfall, the giant concrete goldfish) was slightly different again. But here too Anwar was very much in the driver's seat.

In the end, we worked very carefully with the giant goldfish, presenting motifs from a half- forgotten dream. Anwar's beautiful nightmare? An allegory for his storytelling confection? For his blindness? For the wilful blindness by which almost all history is written, and by which, consequently, we inevitably come to know (and fail to know) ourselves? The fish changes throughout the film, but it is always a world of 'eye candy", emptiness and ghosts. If it could be explained adequately in words, we would not need it in the film.

The Televisi Republik Indonesia 'Special Dialogue" came into being when the show's producers realised that feared and respected paramilitary leaders making a film about the genocide was a big story (they came to know about our work because we were using the TVRI studios.) After their grotesque chat show was broadcast, there was no critical response in North Sumatra whatsoever.

This is not to say that the show will not be shocking to Indonesians. For reasons discussed in my director's statement, North Sumatrans are more accustomed than Jakartans, for example, to the boasting of perpetrators (who in Sumatra were recruited from the ranks of gangsters – and the basis of gangsters' power, after all, lies in being feared).

Anwar and his friends knew that their fiction scenes were only being made for our documentary, and this will be clear to the audience, too. But at the same time, if these scenes were to offer genuine insights, it was vital that the filmmaking project was one in which they were deeply invested, and one over which they felt ownership.

Historical Context

The 1965 – 1966 Massacres in Indonesia

Edited from observations on the massacres, their aftermath and implications, by Historian John Roosa. Additional opening and closing notes by Joshua Oppenheimer.

In 1965, the Indonesian government was overthrown by the military. Sukarno, Indonesia's first president, founder of the non-aligned movement, and leader of the national revolution against Dutch colonialism, was deposed and replaced by right-wing General Suharto. The Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), which had been a core constituency in the struggle against Dutch colonialism, and which had firmly supported President Sukarno (who was not a communist), was immediately banned.

On the eve of the coup, the PKI was the largest communist party in the world, outside of a communist country. It was officially committed to winning power through elections, and its affiliates included all of Indonesia's trade unions and cooperatives for landless farmers. Its major campaign issues included land reform, as well as nationalising foreign-owned mining, oil, and plantation companies. In this, they sought to mobilise Indonesia's vast natural resources for the benefit of the Indonesian people, who, in the aftermath of three hundred years of colonial exploitation, were, on the whole, extremely poor.

After the 1965 military coup, anybody opposed to the new military dictatorship could be accused of being a communist. This included union members, landless farmers, intellectuals, and the ethnic Chinese, as well as anybody who struggled for a redistribution of wealth in the aftermath of colonialism. In less than a year, and with the direct aid of western governments, over one million of these 'communists" were murdered. In America, the massacre was regarded as a major 'victory over communism," and generally celebrated as good news. Time Magazine reported 'the West's best news for years in Asia," while The New York Times ran the headline, 'A Gleam of Light in Asia," and praised Washington for keeping its hand in the killings well hidden.

(The scapegoating of the ethnic Chinese, who had come to Indonesia in the 18th and 19th centuries, was done at the incitement of the US intelligence services, which sought to drive a wedge between the new Indonesian regime and the People's Republic of China. The slaughter of village-level members of the PKI and its affiliate unions and cooperatives was also encouraged by the US, who was worried that without a 'scorched earth" approach, the new Indonesian regime might eventually accommodate the PKI base.)

In many regions of Indonesia, the army recruited civilians to carry out the killings. They were organised into paramilitary groups, given basic training (and significant military back up). In the province of North Sumatra and elsewhere, the paramilitaries were recruited largely from the ranks of gangsters, or 'preman." Ever since the massacres, the Indonesian government has celebrated the 'extermination of the communists" as a patriotic struggle, and celebrated the paramilitaries and gangsters as its heroes, rewarding them with power and privilege. These men and their protégés have occupied key positions of power – and persecuted their opponents – ever since. The pretext for the 1965-66 genocide was the assassination of six army generals on the night of 1 October, 1965.

1.10.1965: The Thirtieth of September Movement (Gerakan 30 September, or G30S), made up of disaffected junior Indonesian Armed Forces Officers, assassinated six Indonesian Army Generals in an abortive coup and dumped their bodies down a well south of the city. At the same time, the Movement's troops took over the national radio station and announced that they intended to protect President Sukarno from a cabal of right-wing army generals plotting a seizure of power. The Movement was defeated before most Indonesians knew it existed. The senior surviving army commander, Major General Suharto, launched a quick counter-attack and drove the Movement's troops from Jakarta within one day.

1.10.1965: The Thirtieth of September Movement (Gerakan 30 September, or G30S), made up of disaffected junior Indonesian Armed Forces Officers, assassinated six Indonesian Army Generals in an abortive coup and dumped their bodies down a well south of the city. At the same time, the Movement's troops took over the national radio station and announced that they intended to protect President Sukarno from a cabal of right-wing army generals plotting a seizure of power. The Movement was defeated before most Indonesians knew it existed. The senior surviving army commander, Major General Suharto, launched a quick counter-attack and drove the Movement's troops from Jakarta within one day.

Suharto accused the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) of masterminding the Movement and then orchestrated an extermination of persons affiliated with the party. Suharto's military rounded up over a million and a half people, accusing all of them of being involved in the Movement. In one of the worst bloodbaths of the 20th century, hundreds of thousands of individuals were massacred by the army and its affiliated militias, largely in Central Java, East Java, Bali, and North Sumatra from late 1965 to mid-1966. In a climate of national emergency, Suharto gradually usurped President Sukarno's authority and established himself as the de facto president (with the power to dismiss and appoint ministers) by March 1966.

The massacres were out of all proportion to their ostensible cause. The Movement was a small-scale conspiratorial action organised by a handful of people. In total, it killed twelve people. Suharto exaggerated its magnitude until it assumed the shape of an ongoing, nation-wide conspiracy to commit mass murder. All the millions of people associated with the PKI, even illiterate peasants in remote villages, were presented as murderers collectively responsible for the Movement.

Indonesian government and military officials, to the very end of the Suharto regime in 1998, invoked the spectre of the PKI in response to any disturbance or sign of dissent. The key phrase in the regime's argument was 'the latent danger of communism." The unfinished eradication of the PKI was, in a very real sense, the raison d'être of the Suharto regime. The original legal act under which the regime ruled Indonesia for over thirty years was Sukarno's presidential order of 3rd October 1965, authorising Suharto to 'restore order." That was an emergency order. But for Suharto, the emergency never ended.

In constructing a legitimating ideology for his dictatorship, Suharto presented himself as the savoir of the nation for having defeated the Movement. His regime incessantly drilled the event into the minds of the populace by every method of state propaganda: textbooks, monuments, street names, films, museums, commemorative rituals and national holidays. The Suharto regime justified its existence by placing the Movement at the centre of its historical narrative and depicting the PKI as ineffably evil. Under Suharto, anti-communism became the state religion, complete with sacred sites, rituals, and dates.

It is remarkable that the anti-PKI violence, as such a large-scale event, has been so badly misunderstood. No doubt, the fact that both military personnel and civilians committed the killings has blurred the issue of responsibility. Nonetheless, from what little is already known, it is clear that the military bears the largest share of responsibility and that the killings represented bureaucratic, planned violence more than popular, spontaneous violence. The Suharto clique of officers, by inventing false stories about the Movement and strictly controlling the media, created a sense among civilians that the PKI was on the warpath. If there had not been this deliberate provocation from the military, the populace would not have believed the PKI was a mortal threat since the party was passive in the aftermath of the Movement. (The military worked hard to whip up popular anger against the PKI from early October 1965 onwards; and the US Government actively encouraged the Indonesian military to pursue rank and file communists). It prodded civilian militias into acting, gave them assurances of impunity, and arranged logistical support.

Contrary to common belief, frensied violence by villagers was virtually unheard of. Suharto's army usually opted for mysterious disappearances rather than exemplary public executions. The army and its militias tended to commit its large-scale massacres in secret: they took captives out of prison at night, trucked them to remote locations, executed them, and then buried the corpses in unmarked mass graves or threw them into rivers.

The tragedy of modern Indonesian history lies not just in the army-organised mass killings of 1965-66 but also in the rise to power of the killers, of persons who viewed massacres and psychological warfare operations as legitimate and normal modes of governance. A regime that legitimated itself by pointing to a mass grave at the site of the well, vowing 'never again," left countless mass graves from one end of the country to the other, from Aceh on the western edge to Papua on the eastern edge. The occupation of East Timor from 1975 to 1999 similarly left tens, if not hundreds, of thousands dead, many anonymously buried. Each mass grave in the archipelago marks an arbitrary, unavowed, secretive exercise of state power.

The obsession with a relatively minor event (the Movement) and the erasure of a world-historical event (the mass killings of 1965-66) has blocked empathy for the victims, such as the relatives of those men and women who disappeared. While a monument stands next to the well in which the Movement's troops dumped the bodies of the six army generals on October 1, 1965, there is no monument to be found at the mass graves that hold the hundreds of thousands of persons killed in the name of suppressing the Movement.

Focus on who killed the army generals on 30th September, 1965 has functioned as a fetish, displacing all attention from the murder of over one million alleged communists in the months that followed. Suharto's regime produced endless propaganda about the brutal communists behind the killing of the generals, and still today most discussion of the genocide has been displaced by this focus. And this is true even in most English-language sources. To me, participating in the debate around 'who killed the generals" feels grotesque, which is why it does not feature in The Act Of Killing. The Rwandan genocide was triggered when Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana (a Hutu) died after his airplane was shot down on its approach to Kigali. To focus on who shot down the plane (was it Tutsi extremists? was it Hutu extremists acting as provocateurs?) rather than the murder of 800,000 Tutsis and Hutu moderates over the next 100 days would be unconscionable. Similarly, who started the Reichstag fire is irrelevant to an understanding of the Holocaust. Whether or not the disgruntled army officers behind the killing of the six generals had the support of the head of the PKI is much more than beside the point: it plays the pernicious role of deflecting attention from a mass murder of world-historical importance. Imagine if, in Rwanda, the fundamental question about what happened in 1994 was 'who shot down the president's plane?" This would only be thinkable if the killers remained in power.

The Act Of Killing

Release Date: October 3rd, 2013

MORE

- Mission: Impossible Fallout

- Glenn Close The Wife

- Allison Chhorn Stanley's Mouth Interview

- Benicio Del Toro Sicario: Day of the Soldado

- Dame Judi Dench Tea With The Dames

- Sandra Bullock Ocean's 8

- Chris Pratt Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom

- Claudia Sangiorgi Dalimore and Michelle Grace...

- Rachel McAdams Disobedience Interview

- Sebastián Lelio and Alessandro Nivola...

- Perri Cummings Trench Interview